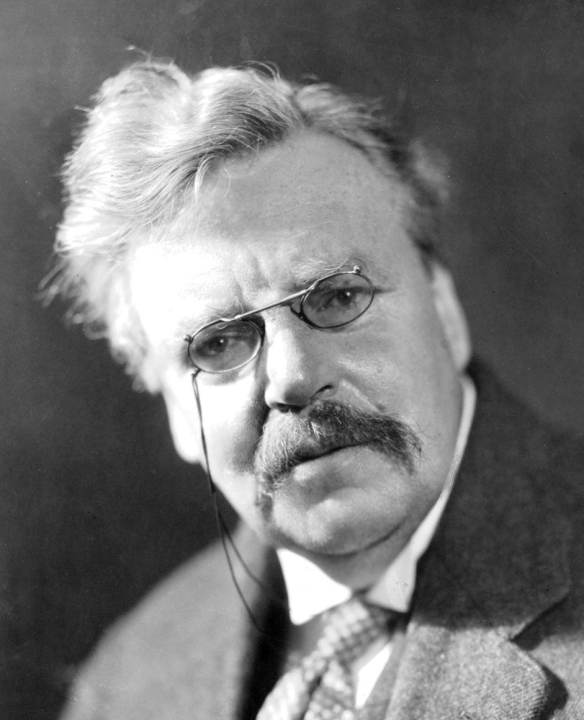

My facebook buddy, the blogger Brandon Vogt, recently posted the video above on Facebook. I was surprised to find out there is a video of Chesterton, best known for his The Everlasting Man, Orthodoxy, and biographies of Aquinas and Francis. It seems like like he’s too big a personality, wellnigh mythical, to fit on film.

Apparently Chesterton’s cause for canonization is being advanced in Rome these days. It’s not surprising given how much influence he has exerted on Catholic writers, popes (including the present pope), and even atheist authors such as Slavoj Zizek whose The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity is heavily influenced by the English Catholic writer.

“Wha? Zizek?!,” says Chesterton in an aside in his still wildly popular Orthodoxy.

Chesterton is generally known as an all-around funny guy who wrote on serious topics in a way that could get anyone interested in the adventurous minutiae of orthodoxy. It’s an effective writing strategy that can catch opponents off guard. I’ve seen his writing style compared to Kierkegaard recently. Apparently there isn’t anything new in this comparison, because specialists were making it a long time ago.

In the video Chesterton is proclaimed “One of the foremost crusaders of modern letters.” When I first heard the video I thought he was being proclaimed a “dictator.” In hindsight his response to receiving the honor doesn’t seem funny or effective. It leaves me more uncomfortable than if he had been proclaimed dictator of letters, “I can only say that I am not much of a Crusader, but at least I am not a Mohammedan.”

You might or might not remember that the First Crusade (1096–1099) began as a pilgrimage and ended as a military expedition by Roman Catholic Europe to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquests of the seventh century. Jerusalem was recaptured in 1099. Subsequent Crusades followed and resulted not only in more rifts between the Rome and Islam, but ultimately also between Rome and the Christian East.

The Lost History of Christianity tells the millennium long Christian tale of lands we usually consider Muslim.

One cannot help but think of how the intersections of Christian and Muslim history have always been marked by violent conflict, starting with the minor conquests of Mohammad of what used to be Jewish-Christian and pagan lands. Philip Jenkins, ever the myth-buster, has also written a book about what happened afterwards, The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia–and How It Died. We tend to track the progress of Christianity in these lands with much interest, since they are some of the biggest growth areas in the world. However, they have a long history both we and they can tap into.

Now one might say Islam started with about five hundred years of victories, only to be followed by steady and depressing slide into defeat that still continues. The decimation of non-Western Christianities seems to be more of a desperate lashing out by certain factions within Islam than anything else. It’s also a sad fact that the vast majority of Western Christians have only become aware of non-Western Christianities only as they are being destroyed. For example, in the wake of the American occupation of Iraq, and more recently in the much covered events in the areas surrounding Cairo.

How should we respond to these sorts of situations? Will violent intervention by the US help the Copts? Or will it just create more resentment toward Christians in the region? Then again, will Western Christians just sit by and watch the decimation of these communities?

And so given the history of violence between Islam and Christianity in the region is there much hope for a resolution, or is it a zero-sum game? If Christ is the Prince of Peace, then is it too much to ask the people of Egypt and other places to suffer martyrdom? Then again, if we do believe the promises of the New Testament could this be the most rational thing to ask of them? Do they believe that? Do we? Should we?

From what I was able to gather from the reports this might be a picture from one of the churches that had to cancel its liturgies.t’s been reported that Egyptian churches interrupted 1,600 years of continuous liturgies this past Sunday due to the violence.

As we ponder these questions it’s been recently reported that Egyptian churches interrupted 1,600 years (!) of continuous liturgies this past Sunday due to the violence. Whatever the solution might be, Chesterton’s irreverent triumphalism (it had its place after centuries of anti-Medieval Enlightenment propaganda) in this video is probably not up to snuff when facing the complexities of the choices ahead, or the consequences of inaction.

This is not an attempt to take Chesterton down a notch, because he remains a highly innovative and relevant theologian. It’s just that the level of comfort he, and the Inklings who followed him, felt when it came to Christian miliatarism is something we cannot afford after World War II and Hiroshima (or, at least I like to think so).

“Radner’s A Brutal Unity is at a book of startling insight, extraordinary erudition, and is replete with theological implications. His ability to help us see connections between Christian disunity and liberal political theory and practice should command the attention of Christian and non-Christian alike. A Brutal Unity is a stunning achievement.”

–Stanley Hauerwas, Duke Divinity School

One possible avenue of reflection and a source of humility in such times is Ephraim Radner’s recent book, A Brutal Unity: The Spiritual Politics of the Christian Church. Matthew Levering has said the following about it:

“Massively learned and beautifully written, this book has to be the best work ever written against the holiness and unity of the Church by a Christian theologian. Not one to mince words, Radner presents Judas as the mirror of the faithless, violent, and fractured Church. For Radner, the failure of liberalism arises from and reflects the failure of the Church to repent. But he does not end here: he argues that in God’s creation of things separate from God, and in Christ’s radical giving of himself, we find God’s holiness and oneness as a gift for God’s people and as an invitation to imitate God’s asymmetrical giving. Those who disagree with Radner will thank him for pressing us to examine anew why Christians rightly confess the Church to be one and holy.”

Do you have any other guides for reflection or action?

======================================

Update et mea culpa: I think the ignorance of Western Christians about these other traditions is best exemplified by the fact that I initially used “we” where I now use “Western Christians” in the following sentence: “It’s also a sad fact that the vast majority of Western Christians have only become aware of non-Western Christianities only as they are being destroyed.”

My thanks go out to Joseph Koczera, SJ for catching this mistake.

Roger Scruton: “The Uses of Pessimism.” http://www.amazon.com/The-Uses-Pessimism-Danger-False/dp/0199968977/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1377051770&sr=8-1&keywords=roger+scruton+the+uses+of+pessimism

I think this is the other side of the debate–I see in the Cavanaugh/Radner strands of the relation of Church/state/culture a tendency to totally dismiss the “two swords” tradition in Christendom as totally spent up and dead. While they may not be advocating out and out quietism or fidiesm (I know this is often what they are accused of–I studied under Dr. Hauerwas long enough to know these accusations do not hit the mark), the Church-as-alternative-community narrative is not obviously the only choice left, nor is it necessarily the only explanation of events. I think it too often conflates political society and civil society–so strangely enough, for all its pointing to the all-consuming nature of liberalism, it will say things like “the Church must be its own politics,” therefore making politics and culture the same kind of thing.

In Catholic social teaching of course, political society should be at the service of civil society, and the impulse to reduce all prerogatives of human life to the atomistic individual or the atomistic state runs rampant not only on the intermediate institutions so integral to tranquility of order imagined by Augustinian and Thomistic social imagination, but severely over-estimates the legitimate hopes we can hope to obtain by political means.

To my mind, Scruton illustrates this need for restraint beautifully. His book made me see clearly, for the first time, that hope is a Theological virtue, that is not incompatible with pessimism (i.e. Augustine’s City of God), and it is often optimism that replaces or suppresses hope, precisely by demanding too much from politics, or history, or culture, etc.

Just a thought! Blessings!

What are the approaches you’d recommend for Western Christians in response to what’s been happening to MIddle-Eastern Christians?

Unfortunately, every time I begin to think of an approach, it just sounds like various cop-outs at this point:

On one hand, I want to say something important I learned from Dr. Hauerwas, which essentially is not to use a bad case to make a good point. In his ethics class (and the example he gave is something I saw with my own eyes in undergrad philosophy), he draws the old standard train track dillema (or some other version of the “trolley problem”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem), and proceeds to show how ridiculous it is to decide whether you are a utilitarian or deontologist (or whatever) by deciding what you would do in a dillema, when it was a thousand little things that make up the true moral question (of course, this is how he transfers the discussion into virtue ethics). In other words some things are moral catastrophes or tragedies, and they make bad “standard cases” as it were. And my first impulse is to say that the particular situation on the ground now is something similar, that most approaches, be they Radner-like or Scruton-like, address issues that build up to these catastrophes, rather than actively solve them.

BUT this not only does the folks on the ground no good, this sort of thing simply happens too much (and as history shows, too cyclically with Christianities that rub shoulders with Islam) to write off as a mere “bad examples” for our moral theories.

Aristotle predicts all of this, says the science of ethics cannot determine particulars before they happen, and is thus an outline and encouragement to cultivate the virtues before we face moral difficulties, and that moral and political goods are hard to come by and even more difficult to maintain, echoing his master’s dictum “All beautiful things are difficult and prone to fail.” But while it is important for us with power to remember this, that we are not the “world’s solution,” this all comes off as cold comfort to people currently going through violent disruption in the tranquility of order in their nations.

But my worries aside, I think a very practial thing to remember is that democracy is not revealed religion, and we are not failing our mission as Christians, nor as Americans, nor as Westerners, nor as practicioners of democracy if we admit that this particular form of government is not the best for everyone (whether we think it is the best form of government or not…don’t get me started on that yarn!). The idealism and optimism that acts like democracy solves all problems (just like the idea that national independence solves all problems or internationalism solves all problems, etc.) costs human lives to entertain. People get confused about the principle that evil cannot be used to obtain another good and the tolerance of evil (tolerance being another term much maligned)–tolerating the fact that no Bathist secular despot is a poster child of a Magnanimous and Just ruler is not the same as using an evil for a good. It is the same principle that says more evil would come than good if we were to execute every person who ran afoul of any particular legislation of the natural law–hunting down every onanist on earth would not only deplete the resources of every government on earth, it would cause other evils that can only be imagined. And thus, governments tolerate onanists and the Church is not required to stick their nose up and refuse to particpate in such governments. The same must be said (to a point, and what the point is–well, that is always the hard part, right?) about rulers, most noticably the Assads of the world. Does that mean it is obvious we should support Assad? No, but it is not obvious that he needs ousted and we need to send off rocket launchers simply because he is not rowdy about democracy.

As peace is not merely the absence of war nor some strifeless buddhist nirvana but the tranquility of order (per Pope John XXIII commenting on Augustine), we sometimes have to be honest about some lackluster form or office-holder of government being the most likely candidate to be the person who maintains the most tranquility avaialbe to a particular time and place. This sort of political pessimism will keep us out of more wars, and may (but who knows?) lesson agitations in the middle east that usually end up with the blood of Jews and Christians being spilt. This is not an attractive world to sell in terms of the big picture, but I think it is a more honest world.

But what about complacency with atrocities? What if this new Egyptian General is the man to stabilize civil and political society (the Copts seems to think this is the case), but only after civil war and brutaility committed by the people under his command? I don’t know the answer to this one, becuase I don’t know what to actively do about it. I know that as there is not even a half unified Christendom anymore, there is no one who could even imagine to say “we will fight on the side of the generals in order to save our Christian brothers.” So instead, there is shadow play and ruminations either about “national interest” or “Democratic principles,” and both seem petty and contemptous.

and just to make the point how difficult this all is:

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/killing-the-copts/?utm_source=feedly

Pingback: Thursday, August 22, 2013 | Tipsy Teetotaler

Pingback: TOP 10: Corrections to Peter Kreeft’s Contemporary Philosophy List! | Cosmos the in Lost