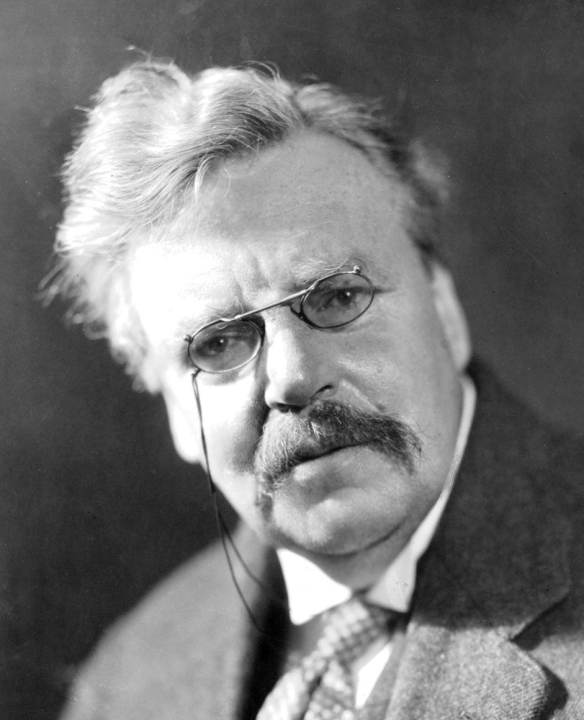

My facebook buddy, the blogger Brandon Vogt, recently posted the video above on Facebook. I was surprised to find out there is a video of Chesterton, best known for his The Everlasting Man, Orthodoxy, and biographies of Aquinas and Francis. It seems like like he’s too big a personality, wellnigh mythical, to fit on film.

Apparently Chesterton’s cause for canonization is being advanced in Rome these days. It’s not surprising given how much influence he has exerted on Catholic writers, popes (including the present pope), and even atheist authors such as Slavoj Zizek whose The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity is heavily influenced by the English Catholic writer.

“Wha? Zizek?!,” says Chesterton in an aside in his still wildly popular Orthodoxy.

Chesterton is generally known as an all-around funny guy who wrote on serious topics in a way that could get anyone interested in the adventurous minutiae of orthodoxy. It’s an effective writing strategy that can catch opponents off guard. I’ve seen his writing style compared to Kierkegaard recently. Apparently there isn’t anything new in this comparison, because specialists were making it a long time ago.

In the video Chesterton is proclaimed “One of the foremost crusaders of modern letters.” When I first heard the video I thought he was being proclaimed a “dictator.” In hindsight his response to receiving the honor doesn’t seem funny or effective. It leaves me more uncomfortable than if he had been proclaimed dictator of letters, “I can only say that I am not much of a Crusader, but at least I am not a Mohammedan.”

You might or might not remember that the First Crusade (1096–1099) began as a pilgrimage and ended as a military expedition by Roman Catholic Europe to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquests of the seventh century. Jerusalem was recaptured in 1099. Subsequent Crusades followed and resulted not only in more rifts between the Rome and Islam, but ultimately also between Rome and the Christian East.

The Lost History of Christianity tells the millennium long Christian tale of lands we usually consider Muslim.

One cannot help but think of how the intersections of Christian and Muslim history have always been marked by violent conflict, starting with the minor conquests of Mohammad of what used to be Jewish-Christian and pagan lands. Philip Jenkins, ever the myth-buster, has also written a book about what happened afterwards, The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia–and How It Died. We tend to track the progress of Christianity in these lands with much interest, since they are some of the biggest growth areas in the world. However, they have a long history both we and they can tap into.

Now one might say Islam started with about five hundred years of victories, only to be followed by steady and depressing slide into defeat that still continues. The decimation of non-Western Christianities seems to be more of a desperate lashing out by certain factions within Islam than anything else. It’s also a sad fact that the vast majority of Western Christians have only become aware of non-Western Christianities only as they are being destroyed. For example, in the wake of the American occupation of Iraq, and more recently in the much covered events in the areas surrounding Cairo.

How should we respond to these sorts of situations? Will violent intervention by the US help the Copts? Or will it just create more resentment toward Christians in the region? Then again, will Western Christians just sit by and watch the decimation of these communities?

And so given the history of violence between Islam and Christianity in the region is there much hope for a resolution, or is it a zero-sum game? If Christ is the Prince of Peace, then is it too much to ask the people of Egypt and other places to suffer martyrdom? Then again, if we do believe the promises of the New Testament could this be the most rational thing to ask of them? Do they believe that? Do we? Should we?

From what I was able to gather from the reports this might be a picture from one of the churches that had to cancel its liturgies.t’s been reported that Egyptian churches interrupted 1,600 years of continuous liturgies this past Sunday due to the violence.

As we ponder these questions it’s been recently reported that Egyptian churches interrupted 1,600 years (!) of continuous liturgies this past Sunday due to the violence. Whatever the solution might be, Chesterton’s irreverent triumphalism (it had its place after centuries of anti-Medieval Enlightenment propaganda) in this video is probably not up to snuff when facing the complexities of the choices ahead, or the consequences of inaction.

This is not an attempt to take Chesterton down a notch, because he remains a highly innovative and relevant theologian. It’s just that the level of comfort he, and the Inklings who followed him, felt when it came to Christian miliatarism is something we cannot afford after World War II and Hiroshima (or, at least I like to think so).

“Radner’s A Brutal Unity is at a book of startling insight, extraordinary erudition, and is replete with theological implications. His ability to help us see connections between Christian disunity and liberal political theory and practice should command the attention of Christian and non-Christian alike. A Brutal Unity is a stunning achievement.”

–Stanley Hauerwas, Duke Divinity School

One possible avenue of reflection and a source of humility in such times is Ephraim Radner’s recent book, A Brutal Unity: The Spiritual Politics of the Christian Church. Matthew Levering has said the following about it:

“Massively learned and beautifully written, this book has to be the best work ever written against the holiness and unity of the Church by a Christian theologian. Not one to mince words, Radner presents Judas as the mirror of the faithless, violent, and fractured Church. For Radner, the failure of liberalism arises from and reflects the failure of the Church to repent. But he does not end here: he argues that in God’s creation of things separate from God, and in Christ’s radical giving of himself, we find God’s holiness and oneness as a gift for God’s people and as an invitation to imitate God’s asymmetrical giving. Those who disagree with Radner will thank him for pressing us to examine anew why Christians rightly confess the Church to be one and holy.”

Do you have any other guides for reflection or action?

======================================

Update et mea culpa: I think the ignorance of Western Christians about these other traditions is best exemplified by the fact that I initially used “we” where I now use “Western Christians” in the following sentence: “It’s also a sad fact that the vast majority of Western Christians have only become aware of non-Western Christianities only as they are being destroyed.”

My thanks go out to Joseph Koczera, SJ for catching this mistake.