You’ve been warned.

I’ve recently written on both heaven and on hell. My own readings on these topics might be idiosyncratic. I’m not sure whether these books get read in seminaries or comparative religion programs. I don’t even know whether these topics are of any interest to academics in those disciplines. I, for one, went through most of the classes offered on Christianity at the University of Washington’s excellent Comparative Religion program and didn’t encounter, or discuss, anything about these topics. What follows is a list of books (in no particular order) I’ve found helpful for thinking about heaven and hell (along with their publisher blurbs).

Please order books via the links provided here if you’d like to help put some diapers on little Rosman butts!

HELL

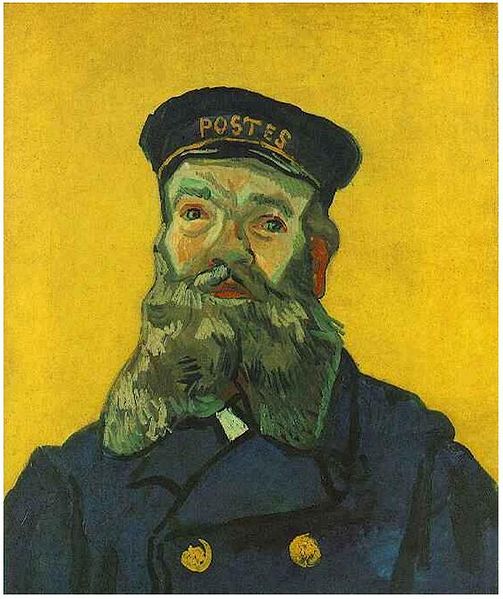

JBR is the dean of devil studies. This is the summary book from his five volume history of the topic.

“[In The Prince of Darkness] Russell recreates the arcane images of good and evil we all once understood perfectly well as children. From the moment the cover is lifted on this beautifully produced book, the world darkens. Russell presents story after story, using them like a descending staircase, drawing us down into archetypal memories of unending battles with the Evil One.”—Bloomsbury Review

Are you ready to RUMBLE?!

“[The Old Enemy is a] learned . . . but also robust book. . . . Forsyth is much at home amid the heroics, graphic laments and winged enormities and leviathans of the Sumerian, Hittite and Canaanite epic fables. . . . He sees the narrative links between Marduk and Zeus, between the death-king Mor and the classical underworld. At the close of the study, the chapters on Augustine glow with intelligence and sympathy.”—George Steiner, The Times Literary Supplement

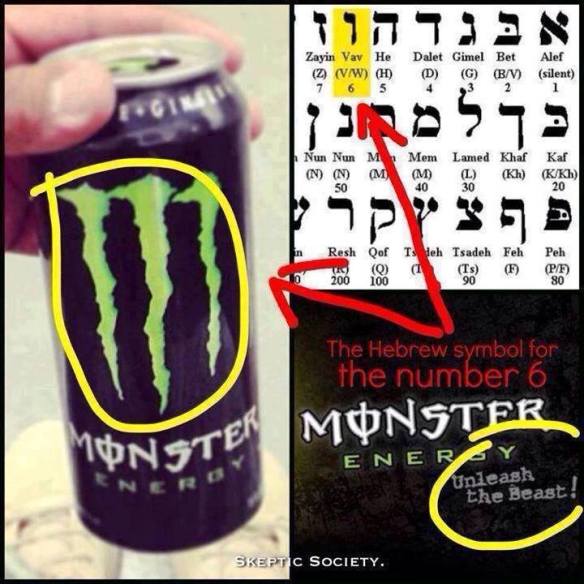

What the?

“This book displays the breath and breadth of life in history more than any merely analytical study could do. [The Formation of Hell] illuminates and deepens us with its humanity and its rare lucidity of style.”—Jeffrey Burton Russell

The prince of philosophical prose. Nobody keeps you interested in abstruse problems like Kolakowski.

“[Kolakowski’s] exploration of the philosophy of religion covers the historical discussions of the nature and existence of evil, the importance of the concepts of failure and eternity to the religious impulse, the relationship between skepticism and mysticism, and the place of reason, understanding, and in models of religious thought. He examines why people, throughout known history, have cherished the idea of eternity and existence after death, and why this hope has been dependent on the worship of an eternal reality. He confronts the problems of meaning in religious language.”

He’ll make you a believer in the (non?-)existence of Satan.

“Rene Girard is beyond question one of the seminal Christian thinkers of our time. Few, if any, have more imaginatively engaged the dominant ideas of modernity and post-modernity by exploring the bilical telling of the human story. He is one of those writers who, once discovered, leaves an indelible mark on one’s mind and soul. Read I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, and be prepared to be changed.”—Richard John Neuhaus, First Things

HEAVEN

Zaleski is our premier guide to otherworld journeys.

“Critics of religion have argued that Christianity’s success stems from its promise of eternal life, that people become Christian at bottom merely to cope with their fear of death. Contemporary theologians and philosophers, highly sensitive to this charge, tend to skirt the issue of life after death. To speak of the afterlife is at best to engage in wishful thinking, at worst to descend to the level of pop religion, encounters with angels, and UFO abductions. In The Life of the World to Come, however, Carol Zaleski asks the question, ‘Are we rationally and morally entitled to believe in life after death?’ and answers with a spirited and emphatic ‘yes.'”

Much more fun than his book on sin and guilt. Also one of the nicest people I’ve ever met.

“With erudition and wit, Jean Delumeau’s History of Paradise explores the medieval conviction that paradise existed in a precise although unreachable earthly location. Delving into the writings of dozens of medieval and Renaissance thinkers, from Augustine to Dante, Delumeau presents a luminous study of the meaning of Original Sin and the human yearning for paradise. The finest minds of the Middle Ages wrote about where paradise was to be found, what it was like, and who dwelt in it. Explorers sailed into the unknown in search of paradisal gardens of wealth and delight that were thought to be near the original Garden.Cartographers drew Eden into their maps, often indicating the wilderness into which Adam and Eve were cast, along with the magical kingdom of Prester John, Jerusalem, Babel, the Happy Isles, Ophir, and other places described in biblical narrative or borrowed from other cultures. Later, Renaissance thinkers and writers meticulously reconstructed the details of the original Eden, even providing schedules of the Creation and physical descriptions of Adam and Eve. Even when the Enlightenment, with its discovery of fossils and pre-Darwinian theories of evolution, gradually banished the dream of paradise on earth, a nostalgia for Eden shaped elements of culture from literature to gardening.In our own time, Eden’s hold on the Western imagination continues to fuel questions such as whether land should be conserved or exploited and whether a return to innocence is possible.”

The man who brought you the ultimate itinerary of the Devil also has a handle on heaven.

“At minimum, it is the most rigorous modern study of the various strains of Western tradition that culminate in [Dante’s] Paradiso. But its introductory chapter [of A History of Heaven] goes beyond that to sketch out an apologia for passionate heavenly belief. In effect, Russell tries to re-establish the honor of the Christian mystical tradition. . . . Like Dante’s, Russell’s paradise is deeply God-oriented. . . .”—David Van Biema, Time

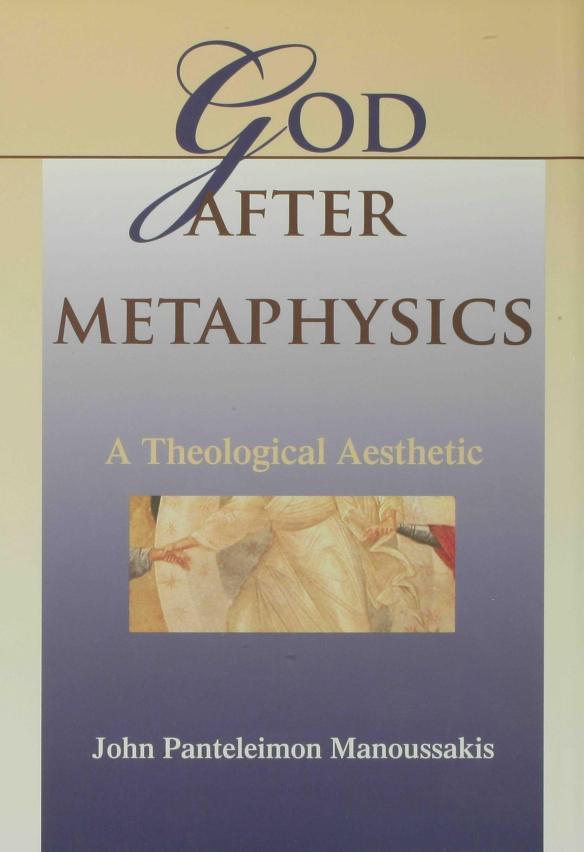

A slightly more philosophical guide through the significance of the afterlife for the present life.

“Nicodemus first posed the question “How can anyone be born after having grown old? Can one enter a second time into the mother’s womb and be born?” This book reads that problem in the context of contemporary philosophy (particularly the thought of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze). The phenomenology of the body born ‘from below’ is seen as a paradigm for a theology of spiritual rebirth, and for rebirth of the body from ‘on high.’ [The Metamorphosis of Finitude argues] the Resurrection changes everything in Christianity–but it is also our own bodies that must be transformed in resurrection, as Christ is transfigured. And the way in which I hope to be resurrected bodily in God, in the future, depends upon the way in which I live bodily today.”

Death, you lose!

“Levering brings the best of current biblical scholarship into a creative interface with theological reflection informed by one of the Church’s greatest minds, Thomas Aquinas. In Jesus and the Demise of Death the core tenets of classical Christian eschatology, recently jettisoned by many theologians as allegedly outdated, make a surprising and come-back. Levering adds an important and timely Catholic contribution to the lively contemporary theological debate about Christian eschatology.”—Reinhard Huetter

Don’t miss our top 10 books (that I’ve read) of the last 10 years.

But remember, a different faith means a different afterlife:

I couldn’t get a preview of the video link below. So here’s a sneak peak.

http://en.gloria.tv/?media=93470