What follows is an essay I published with IMAGE Journal with the help of the Starmach Gallery in Krakow (You too can own a Nowosielski!).

IMAGE needs your generous emergency donations more than ever. They are in serious financial trouble through no fault of their own. I know many of you read IMAGE, so please step up.

Jerzy Nowosielski. Wings of the Archangel, 1947. Oil on canvas.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-bye;

And further still at an unearthly height,

A luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

—Robert Frost

Lately I’ve become acquainted with the night coursing through my veins. Like any good diabetic, I have to draw murky drops of blood several times daily to measure my sugar levels. This all began with a hospital visit some seven months ago. That was when I discovered my bloody secret. Around midnight I was led into a darkened hospital room which would be my home for the next week. My two octogenarian companions lay sleeping. Their diapers filled our temporary camp with a smell that outdid anything the corpse of Father Zosima could have emitted.

You might wonder what a grad-student-for-life does in situations like these. He reads this in Nietzsche’s The Gay Science: “After Buddha was dead people showed his shadow for centuries afterwards in a cave—an immense frightful shadow. God is dead: but as the human race is constituted, there will perhaps be caves for millenniums yet, in which people will show his shadow.” The Prussian was probably right. The shadow of God has accompanied me since time out of mind, yet I continually reach for his light—never overcoming the shadowy impression that I’m neither quite wrong, nor really ever right.

The Bible’s sacred history is typically associated with the metaphor of light—the blinding light of revelation banishing darkness. But what, someone might ask, does revelation have to do with the murky ambiguity of so much human experience? For many of us, the light of revelation seems to leave the dim regions of our lives untouched. The paintings of Jerzy Nowosielski address the shadowy, opaque dimensions of experience. His art proposes a spectral shift in our reading of the biblical story—and therefore of our own stories. Nowosielski’s paintings seem to imply that there is something deeply human, and therefore perhaps also divine, about the darker aspects of our existence. No wonder one Polish art critic called him “the most secular religious artist and the greatest theologian among secular artists.”

But before we look at his paintings, we should dim the lights theologically. If we look at the foundational events of the Bible, the ones that guide the lives of Jews and Christians, we cannot help but notice the obscure register that reigns there: God appears to be a creature of the night, hidden when he reveals himself, seen “as through a glass, darkly.” One of the first things we read is, “Darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” A bit later, the foundation of the Israelite religion is built upon Moses receiving the tablets from a God clad in a cloud of darkness. During the Exodus, God’s people are saved by the dark waters which consume Pharaoh’s soldiers. Think also of Jesus in Mary’s dark womb, the dark night of the nativity, the midday darkness falling upon the land during the crucifixion, the darkness of the tomb and the descent into hell; add to it all the blindness of Paul en route to Damascus. I could multiply the examples here (for example, the Apocalypse, a dark unveiling indeed), but I’ll leave that up to you.

The darkness of the Bible is murky but enriching, a bit like a blood transfusion—and the paintings and icons of Jerzy Nowosielski share this quality. Nowosielski inscribes the canvas with the full range of our fears, disappointments, cruelties, and passions (in both senses of the word). “We must honestly admit to ourselves that we find ourselves on the edge of an immense metaphysical black hole,” he says. Yet something more is going on here: he dips his brush into these dark regions and then proceeds to mix them with a transfusion from the clouded streams around the Sacred Heart. Echoing Dostoyevsky’s dictum that “Beauty will save the world,” he writes: “Everything will capsize into the other side. Only art will help us carry our reality onto that other side. Art will save us.” Grace does not cross nature out; even at the general ressurection, we will still bear the marks of our humiliating sufferings, but then they will be accepted and transfigured—just as Christ still had the marks of his passion after his resurrection.

When I think of abstract painting (with the possible exceptions of Congdon, Kandinsky, and Rothko), I think of a personalized vision that dims all connections with reality. Personally, the schizophrenic solipsism of abstract art can be so bleak that it makes me want to stop reproducing and consider suicide.

So how did somebody like Nowosielski, who trained to become an Orthodox monk and icon writer during World War II in a Kiev monastery, first come to public attention with a series of abstract paintings? These works took the theologically saturated Polish art scene by storm during a 1948 exhibition in Krakow. A long-time resident of that city recently told me that the two poles of Sunday recreation that year were the Dominican church and the gallery where Nowosielski and his like-minded friends, the Krakow Group, displayed their paintings.

Nowosielski said that he lost his faith sometime during the Second World War. Though he never systematically addressed why it happened, he came to see that loss as a religiously fruitful experience. It led him to a state where “there is no metaphysical reality, which in essence is a highly metaphysical state, when the consciousness hits some absolute rock-bottom.” For Nowosielski, the way down turned out to be the same as grappling in the dark for the way up. “I started seeking the metaphysical roots of painting in this state of certain uncertainty about what I’m doing in art and where I stand. That’s when my ‘abstract painting’ was born,” he says. His statement echoes the Eastern Orthodox practice of apophatic mysticism (known in the West as the Via Negativa). In this tradition one begins by “cleaning the house” of one’s mind, negating all images of God and letting go of all ties to the world. Paradoxically, the practice has a positive and practical aim: clearing our minds of the concepts which screen us from the immanent energies of the transcendent God.

In the 1947 painting Wing of the Archangel, playful, wing-like dark blue triangles poke through in several locations, seeming to push out of the blue-gray areas on the sides and bottom of the canvas [see front cover]. This activity creates an expanding, luminous area of subtly variegated blue calm in the center portion. The orange rectangle and triangle just to the right of the middle emanate a sense of controlled passion.

Theology aside, abstract works like these were in part a rebellion against the mandatory Socialist Realist style imposed by the Soviets, kitschy art that papered over the gray reality of life in the Warsaw Bloc after World War II, a land overwhelmed by memories of atrocities and beaten into the ground by brutal foreign domination that would continue for four more decades. Then again, history is always theological. If there is one thing we learn from Nowosielski’s art it’s that there is no clear distinction between the sacred and the profane, believer and atheist. Everything can and must be taken into the eschatological realism proposed by the resurrection. As Karl Barth loved to say, God’s “no” also contains his ever greater “yes.” Nowosielski continued to follow his abstract intuitions throughout his career and later came to see them within a theological horizon. “The angel is abstract painting,” he once said—albeit sometimes a fallen angel.

Plate 1. Jerzy Nowosielski. Woman in Darkness, 1971. Oil on canvas. 31 ½ x 47 ¼ inches.

Nowosielski’s love for painting the female body saves him from an abstract, heavenly escapism. He has painted sportswomen, housewives, women fully dressed, women in front of mirrors, women near windows, half-nudes, nudes, Madonnas, women in the ambivalent situations of ancient mystery rites, even women undergoing torture. As regards the last three categories, he once said that “art must always be suspect, because it redeems hell.” He meant all of his art, but what subject needs more redeeming than our representation of the female body, reproduced endlessly and demeaningly on billboards and internet sites? Something of this predicament is present in Nowosielski’s Woman in Darkness (1971), a work that suggests a coming to terms with painful secrets or fears about the future [see Plate 1]. The painting uses a dividing wall reminiscent of icon painting or the Stations of the Cross. Here, however, the boundaries seem permeable, intertwined. The bodies participate in a circling exchange, like the perichoresis of the Trinity. The ocher body is either screaming at or reconciling herself to the part of herself in blue, divided from her by the deep gray-blue wall. At the same time, some ochre part of herself seems to pass through that wall. She is merging with or emerging from the blue aspects of herself, which are turned away from us in a gesture of shame or despair.

A bold aspect of many of Nowosielski’s secular paintings is how they resemble icons. The rumor is that Eastern Orthodox faithful often complain that they cannot pray with Nowosielski’s actual icons, because his work consciously breaks so many conventions. I must admit that I would have no qualms about praying with one of Nowosielski’s nudes. I believe him when he says, “When it comes to my so-called secular paintings I am convinced that my theology of the body expressed there ‘speaks’ about problems similar to the ones expressed by the pope in words.” (He refers here to the late John Paul II’s collection of 129 Wednesday audiences on the theology of the body in which he says, among other things, that sexuality can potentially be an image of the Trinity.)

Plate 3. Jerzy Nowosielski. Black Half-nude, 1971. Oil on canvas. 39 x 32 ¼ inches.

Compare the theology implicit in Nowosielski’s Black Half-nude (1971) [see Plate 3] with any of the nudes by the consensus nude painter par excellence, Lucian Freud. Freud’s cadaverous nudes, like the rest of his paintings, seem to be overwhelmed by the weight of sin, which they bear reluctantly like the tree which bore the weight of Judas’s body. For example, search for the painting of the pregnant Kate Moss entitled Naked Portrait. What should be an annunciation of life, Freud turns into a bloodless and dispiriting vivisection, despite his almost Polaroid realism. On the other hand, Nowosielski’s Black Half-nude is all the more real for all the elements of iconic abstraction it employs. Thanks to this, there is a gravity to the body which I can only compare with Michelangelo’s Pietà. Then come all the theological quotations: The white towel around her hips resembles a perizonium (the cloth usually worn by Christ on crucifixes). She sits on a heavenly azure seat, an iconic convention of both East and West in early Christian mosaics representing the coronation of the Virgin.

The cloth around her face creates a mix of theological and secular ambiguities. It could be Veronica’s veil with an imprint of a suffering face, invisible to us, or maybe the woman is taking off her blouse. In a secular inversion of da Messina’s Annunciation, perhaps she is anticipating a sexual encounter with the person facing her: the viewer. While enunciating a theology of the body, the painting playfully breaks with the iconic convention of concentrating upon the face and eyes. To paraphrase an Image editorial [from Issue 41], if we cannot incarnate God in our blood, guts, shit, piss, semen, saliva, bellies, knees, and breasts—he vanishes into the ether. Then again, our conventional iconic expectations are not completely denied: her torso, breasts, and shapely stomach are arranged to resemble a face smiling back at us. I don’t know if they’re telling us to change our lives, but that ambiguity is just how Nowosielski would have it. Finally, there is the orange and yellow glow around her, which at first looks like the neon of a red-light district. But the glow also resembles what Pavel Florensky called “admixtureless light”—that is, gold, the color of the backgrounds of icons. And yet, iconic conventions are again turned inside out here. The background is black, and black penetrates most of the body. According to the painter, this mixing of boundaries is part of the plan of salvation, and therefore art: “There is a mysterious bond between sin and holiness. It can be partly seen with the aid of art. Eros illuminates matter, but this cannot be described with words. Some small part of it can be painted.” Then again, the connection between religious art and eroticism has been part of the tradition for a long time, running from the Song of Songs to any number of Saint Sebastians (most notably Mantegna’s), Bernini’s sculptures, and Donne’s poetry, to name just a few examples.

Plate 4. Jerzy Nowosielski. Mountainous Landscape, 1955. Oil on canvas. 25 ½ x 30 ¾ inches.

Despite his redemptive vision, Nowosielski shows a marked pessimism in his landscapes. This is not because he has any distaste for nature. Quite the contrary. Mountainous Landscape (1955) is typical of his complex understanding of the natural world [see Plate 4]. This landscape has less to do with saccharine Hudson River School canvases than T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland—that is, the metaphysical black hole applied to the natural world. The scorched brown of the mountain turns into black. The green pasture is infected by a mold-like brown. The only unspoiled element is the little blue lake at the top of the mountain. A tiny abstraction built into the scene, integrated yet standing apart, it is a small window of hope. From a purely aesthetic vantage point, there is as much alienation here as in all of de Chirico’s claustrophobic cityscapes (which employ similar compositional structures). But why?

The real subject of the painting can be interpreted as absence. Nowosielski’s theoretical writings are especially helpful here. Asking most modern painters to explain the worldview behind their works is usually as fruitful as asking an art critic to paint something: vanity of vanities. But Nowosielski’s writings and paintings co-inhere, one interpreting the other. Poland is a nation where meat is served at almost every meal. Pretty much the only vegetarians are practicing Catholics on Fridays—and this despite a thriving Franciscan community. In this context, one of the more controversial aspects of Nowosielski’s writings is his outrage at our instrumentalization of the animal world. Orthodoxy is historically more sensitive to the suffering of animals and puts an emphasis on the salvation of the whole world: man, animal, vegetable, and rock. Even so, statements like these from Nowosielski have caused considerable outrage among both professional Catholic and Orthodox theologians: “We all participate in the suffering and death of Christ. Animals also participate, as does the whole of nature. For example, the Paschal Man is not named a lamb as a symbol; it is not a symbol! The suffering of animals is the real suffering of God.”

Mountainous Landscape shows us an apocalyptic nightmare of a world without animals—a world after an environmental Armageddon which might not be that far off. In the negative sense, this landscape is also in the image of fallen man, much like the lonely city-wrecks of de Chirico. It is a prophetic lament for a devastated creation and for a humanity unconsciously losing a salvific opportunity through an ecological crisis. The antidote to all of this could be an embrace of the Christian roots of the environmental movement, which cannot and should not be divorced from the doctrine of creation. Rid of its current quasi-soteriological and Manichean tendencies, environmentalism might become more appealing to a wider group of people. Its historic connections with a more generous worldview are there, if one is willing to look. The green and the sustainable-community movements were heavily influenced by the book Small Is Beautiful, published by Catholic economist E.F. Schumacher during the energy crisis of 1973. And there are ecumenical patron saints of conservation waiting in the wings: Seraphim of Sarov, Francis of Assisi and, more recently, Wendell Berry.

Plate 2. Jerzy Nowosielski. City Landscape, 1959. Oil on canvas. 23 x 32 inches.

City Landscape (1959) reverses the schema, showing an urban setting as a desert [see Plate 2]. The streets are sparsely peopled, the trams seem more symbolic than real, scantily clad women (or are they mannequins?) stand behind windows on either side of the street, and a possible flasher or drunkard in a yellow coat walks briskly away from the viewer, as if he has something to hide. Townhouses oppressively press upon the earthy brown of the streets, and at the top of the painting, the tram tracks fork into the shape of a snake’s flickering tongue. The man in white pants and black coat, despite his dandy hat, has downcast eyes and keeps his hands in his pockets in a reserved, modest, self-aware, almost pious gesture. Is he thumbing rosary beads in his pocket? The colors of his outfit are probably not incidental, as a mysterious drama of good and evil plays itself out at the edges of the painting. Why shouldn’t we see this man as a modern-day Saint Anthony, fighting temptation, loneliness, and maybe a hangover in an urban desert? The strange women and the drunkard-flasher seem to fit this motif, and the trams slither like demythologized serpents.

All of this is seen from above, as if from a bird’s-eye, or God’s-eye view. Nowosielski frequently uses this perspective in otherwise lonely and bleak paintings of cities. It forms the impression of a downward movement toward the earth, as if we are seeing through the eyes of one of Wim Wenders’s angels or the “descending Dove” of Charles Williams. Madeleine Delbrel, sometimes called the French Dorothy Day, captures this iconic vision of the modern urban desert better than anyone I have read: “In those crowds marked by the sins of hatred, lust, and drunkenness, we find a desert of silence, and we recollect ourselves with great ease, so that God can ring out his name: Vox clamans in deserto.” Elsewhere she describes the intersection of this desert of urban sin with the dark ray of divine love in words borrowed avant la lettre from Nowosielski: “Our Christian life is a pathway between two abysses. One is the measurable abyss of the world’s rejections of God. The other is the unfathomable abyss of the mysteries of God. We will come to see that we are walking the adjoining line where these two abysses intersect. And we will thus understand how we are mediators and why we are mediators.”

There are chronological and intellectual reasons to save a discussion of Nowosielski’s explicitly religious works for last. First of all, he regained his faith fairly late in his life and creative career, some time in the late 1950s. Also, his journey back to the church, and to icons, was quite original. Surprisingly, the importance of modern art cannot be underestimated here. “Who is responsible for my being this way? Certainly my fate, but also experience, the lessons of surrealism,” he says. Surrealism proved to be a liberating experience for Nowosielski, because it opened him up to viewing art of all periods, especially Orthodox iconography, as a living and anarchically liberating reality. This freed him from the widespread prejudices of nineteenth-century historicism, which saw art simplistically as a march of progress that consigned all so-called “archaic” forms to the dustbin of history. The spiritual pedigree of the modern avant-garde is well attested theoretically and artistically by Kandinsky (among others), a Russian who drew inspiration from icons.

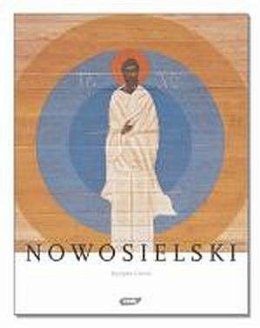

Ever since the late fifties, Nowosielski has consistently produced sacral art of the highest quality and inspiration. However, he had greater aspirations: “From childhood on I dreamed about designing a sacred space. I worked with architects, made polychromes, but these were just fragments. I wanted to create something from the ground up.” Nowosielski got his chance in 1992 in the small town of Biały Bór, population about 2,200. The town is a center of Orthodox and Greek-Catholic culture in northwestern Poland. This unique geographical and cultural situation led Nowosielski to some creative solutions. The dark and womb-like interior has both a traditional and modern feel to it. Its modernity is not in the way of most American churches, which often feel little different from Starbucks.

Plate 5. Jerzy Nowosielski. Church in Biały Bór, Poland, 1992-97. View of Main Nave from the Entrance.

Nowosielski’s modernism digs deep into history without turning into archaeology. The church’s center area, where the liturgy is performed, is notably lower than the raised sides where the faithful congregate [see Plate 5]. This is a direct quotation from the Greek stage, as are the columns and the triple red arches, which imitate the doors through which Greek actors used to enter the stage. It is not incidental that these doors through which the Trinity enters into the drama of the congregation’s lives are colored red, the liturgical color of the Lord’s passion—and also of sexual flush. This understanding of the liturgy as a transforming drama where our salvation and damnation are at stake is confirmed by the artist himself: “As a person who is well nigh obsessively concerned with liturgical questions, I consider the Christian liturgy to be a transformation of the Greek theater, and also as a kind of sacred circus.”

The interior’s color is difficult to render in a photograph, which tends to make it look black; it’s actually a very dark shade of green. In the Orthodox Church green is the liturgical color of several feasts and seasons: the Feasts for Ascetics and Fools for Christ (that is, the holy circus), Pentecost, and Palm Sunday. It is also the liturgical color of hope and resurrection, but as the list suggests, it is a hope achieved by going into the darkness (even the darkness of madness) with God instead of circumventing it with Prozac. At the center is the tetrapod upon which icons are placed for veneration. Directly above, like a top hat floating down upon the congregation below, is a cupola with Christ as Pantokrator. This setting is one of the best spatial representations I know of the Pauline imperative to put on Christ’s mind. Really, it seems like it might fit. We just have to be raised toward it.

Plate 6. Jerzy Nowosielski. Church in Biały Bór, Poland. Exterior.

The exterior facade of the church deliberately resembles an iconostasis (the wall of icons that separates the nave from the sanctuary in an Orthodox church) [see Plate 6]. In part, this is an outgrowth of demographics. During the ordinary parts of the liturgical year the church serves a small congregation. However, during the high holidays, the region’s widely dispersed Polish Greek-Catholic flock comes to this sanctuary. During those times, the church cannot hold the crowd, and so the liturgy moves outdoors. The facade prominently features two archangels flanking a Mandylion. The Mandylion is something like the Orthodox iconic version of the Shroud of Turin. This image, faithfully reproduced by iconographers, shows the imprint of Christ’s face. It is not Veronica’s veil, but a cloth used by Christ to wipe his face during the passion, which was passed along to a servant of King Abgar of Edessa, who was later healed of an incurable sickness thanks to it. It is usually acknowledged as the first and most authentic image, ikon, of Christ. Nowosielski has made many such icons, including one for the Franciscan Church of the Immaculate Conception in Krakow [see Plate 7]. The placing of this image so prominently on the exterior of the church in Biały Bór, facing the elements, invokes for me Nowosielski’s sacrificial logic of the collision of the world with the self-emptying God: “If the earth were not so saturated with evil, there would be no need for the coming of Christ. I am thinking of the kenotic descent of God into such an earth.” The end result of that descent, death, is not easy to swallow, but Christ’s life is normative as an example for anybody who wants to become a Christian. All of reality must be irradiated by the shadow of this suffering face if reality is to be taken up into the life of the Trinity.

Plate 7. Jerzy Nowosielski. Mandylion, 1978. Acrylic paint on board. Franciscan Church of the Immaculate

Conception, Krakow, Poland.

What I have written may seem like an odd art essay, with its swerving into theology, politics, and sex. But the imperative to soil the clean white gloves of high aesthetics is dictated by the oddity of Nowosielski’s art itself, which mishmashes these taboo subjects and opens them up to comparative inquiry. His painting forbids an aestheticized, abstracted “view from nowhere” and instead demands a Christian, personalist engagement with the rough edges of reality. Nowosielski has said that he sees himself as making icons for westerners, for Catholics and Protestants. The West, he says, “properly grasps the spiritual issue of the mystagogical role of art,” an attitude he believes will bear fruit.

Plate 8. Jerzy Nowosielski. Theotokos Oranta with Fathers of the Church, 1984. Greek-Catholic Church in

Lourdes, France.

Several years ago I went to Lourdes with two of my best friends. We did it all: confession, masses, Stations of the Cross, shopping for the finest religious kitsch, and we got dipped in the chilling healing waters. After the bath I noticed a palpable change in myself: I got a sinus infection and spent about two weeks battling it. As we left, I remember seeing a beautiful church with golden cupolas from our moving train. It was Saint Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Church. It immediately charmed me and I wondered what hid inside the dark walls. I had no idea what I missed until I looked at a book of Nowosielski’s works. He painted the whole interior of this little Greek-Catholic church in 1984. Right behind the altar is an immense depiction of the Theotokos in prayer with the Doctors of the Church below her [see Plate 8]. The whole composition is bathed in a deep blue background of a shade that has very little to do with the light-blue ceilings of medieval Catholic churches. Her face is a study in patience learned through suffering. Her eyes (and sinuses) are shadowed by a darkness that she seems to face without flinching, never flagging in the welcoming gesture of her praying arms: she is not afraid of being infected by our sins.

The Greek verb used to describe the making of icons, graphia, means both “to paint” and “to write,” and this is why the whole process is often called “icon writing.” This is how God communicates his image to people in painting. All of it finally brings us to the form of the biblical text, or any other text. Take a look at this page. How is it that the words I write here resound in your mind?

The whiteness of the page is not shouldering the message. It is not the white background, but the ray of darkness of the text which is doing all the work.

Likewise, Nowosielski’s art teaches us to get acquainted with the night of our blood, guts, shit, piss, semen, saliva, minds, gender, environment, cities, diseases, art, and politics, and not fear them, but live them out rightly as the coming of God’s darkness as it incarnates itself within the whole of our mind, body, and soul—especially when they are wracked by suffering. As we contemplate an image like the 1978 Mandylion, its apophatic darkness shows us that our concepts cannot capture the great price and music of the hypostatic union: a God who was fully human, a man who was fully God. In the muddy darkness of daily experience, Nowosielski’s paintings are a visual answer to the question asked by Job: “Where is God my Maker, who gives songs in the night?”

===================================================

Update: I recently noticed that Amazon has one copy of the best catalog of Nowosielski’s work. It’s reasonably priced so snap it up here before someone else does.