In De praescriptione, vii Tertullian asks, ” What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy and the Church?”

As it turns out, quite a lot. Michael J. Buckley in his must-read Denying and Disclosing God: The Ambiguous Progress of Modern Atheism lays out how a too close association between religion and early modern science eventually led to the propagation of atheism.

Yes, you read that right, the relationship was not not marked by antagonism (yet another Enlightenment myth exposed). Poor and mad Giordano Bruno was an exception that proves the rule. The close marriage between science and religion in representative figures such as Galileo, Kepler, and Newton caused trouble for religion, because the arguments of the scientists-believers were impersonal and decontextualized faith in God. Buckley (SJ) believes the natural turf for theological lies elsewhere:

“More astonishing in their absence–within Christian Europe–were the two trinitarian modes of divine self-disclosure and communication: the self-expression of God become an incarnate component within human history or the Spirit transforming human subjectivity in its awareness, affectivity, and experience.”

In other words, in another language, “Du mußt dein Leben ändern.” I’d prefer to see this badly translated as “You must other [verb] your life,” but below you’ll find a more conventional rendition along with the torso of Apollo from the Louvre that inspired Rilke’s ejaculation:

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

The implication of this is that the lives of the saints flesh out the arguments with narratives of changed actions and transformed subjectivities. If religion is not about changing your heart of stone into a heart of flesh, then it’s irrelevant. Buckley approvingly quotes one of Wittgenstein’s letters as recommending such an approach:

“If you and I are to live religious lives, it mustn’t be that we talk a lot about religion, but that our manner of life is different. It is my belief that only if you try to be helpful to other people will you in the end find your way to God.”

In many ways this might be the intention behind the recent words of Pope Francis about the CDF:

“Say you err, [or] make a blunder – it happens! Maybe you’ll receive a letter from the Congregation for Doctrine [sic], saying that they were told this or that thing…. But don’t let it bother you. Explain what you have to explain, but keep going forward…. Open doors, do something where life is calling out [to you].”

However, all of this should not drive a wedge between philosophy and theology when philosophy is properly understood. The temptation is great as the otherwise commendable The Catholic Passion (an attempt at a more fleshly, incarnate, and subjective-transformative approach to theology) demonstrates:

“In this book I chose to go with Claudel [as oppose to writing a commentary on the Baltimore Catechism] to explain Catholicism by way of the experience and faith expressions of real Catholics–saints, composers, poets, playwrights, missionaries, ordinary believers. This approach seems appropriate to Catholicism, which is not a philosophy of life so much as a personal encounter and relationship with a divine person, Jesus. The church’s creeds, dogmas, and doctrines are indispensable–they ensure that this encounter with Jesus is true–but if this neat order of rules and laws is the theorem, then Catholicism’s proof will always be found in what Catholics think and hope for, how they pray, and what they do with their lives.”

The misstatement lies in the opposition between Catholicism and a “philosophy of life.” We must understand philosophy, at least ancient philosophy, but also more recent philosophers such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, in the way Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Epictetus, et al all did, that is, as a way of life, as a set of spiritual exercises, practiced and lived out in philosophic communities.

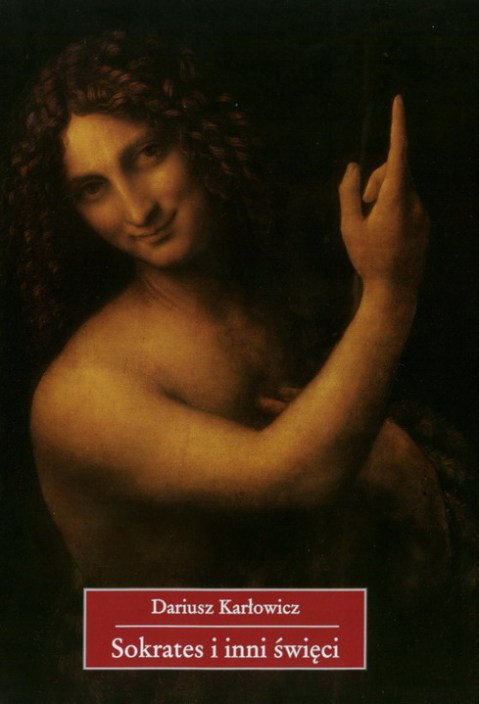

What’s more, Tertullian, for all his anti-philosophical bluster (a style he borrowed from Greek and Roman philosophical schools), actually stole many other things from Athens in the service of Jerusalem. The following passage comes from Dariusz Karłowicz’s Socrates and Other Saints, which I’ve mentioned in a previous post here:

“In Tertullian we can find all the Stoic-Platonic exercises mentioned by Philo of Alexandria. For example: study, meditation (meletai), cures for the passions (therapeiai), recalling the beautiful, self-control, doing one’s duties, or others, such as: listening with a constant attention that is turned upon oneself (prosoche) and indifference toward indifferent things. There was no lack of typical Cynical exercises to combat the passions through bodily mortification. These exercises became so rooted in Christian spirituality that our contemporaries are surprised to discover the ancient philosophical roots of Tertullian’s advice to meditate upon the Lord’s Prayer by first purifying oneself of anger or an unquiet heart. One can confidently say that for Tertullian constant spiritual exercises constitute the content of daily life for members of Christ’s church.”

Step back Harnack.

In related news: Laura Keynes, a great-great-great-granddaughter of the English naturalist Charles Darwin, has gone papist.