My esteemed friend over at Catholic Culture and Society, a blog about organic Catholicism, has been chiding my obsession with the negative aspects of life.

Why not look at a happy integrated family, or the beauty of God’s creation? Why think about violence, death, and perversion?

I confess to writing mostly about the latter. For example, I have written about Nowosielski’s dark iconic vision here, or Kristeva’s obsession with the Baroque here, or dirty Rabelaisian Catholicism here and here, or even Cromwell as Karl Hungus here.

I talk abut these because they are aspects of my own experience that need to be integrated. You should also remember that I come from a country, Poland, that lost roughly one-sixth of its population during World War II.

What follows below is a florilegium that will hopefully suggest Manichean tendencies (of which I’ve been accused) aren’t the only thing behind these posts.

“‘The thought steps in, whether one likes it or no, that death is so terrible and so powerful, that even He who conquered it in His miracles during life was unable to triumph over it at the last. He who called to Lazarus, ‘Lazarus, come forth!’ and the dead man lived—He was now Himself a prey to nature and death. Nature appears to one, looking at this picture, as some huge, implacable, dumb monster; or still better—a stranger simile—some enormous mechanical engine of modern days which has seized and crushed and swallowed up a great and invaluable Being, a Being worth nature and all her laws, worth the whole earth, which was perhaps created merely for the sake of the advent of that Being.

‘This blind, dumb, implacable, eternal, unreasoning force is well shown in the picture, and the absolute subordination of all men and things to it is so well expressed that the idea unconsciously arises in the mind of anyone who looks at it. All those faithful people who were gazing at the cross and its mutilated occupant must have suffered agony of mind that evening; for they must have felt that all their hopes and almost all their faith had been shattered at a blow. They must have separated in terror and dread that night, though each perhaps carried away with him one great thought which was never eradicated from his mind for ever afterwards. If this great Teacher of theirs could have seen Himself after the Crucifixion, how could He have consented to mount the Cross and to die as He did? This thought also comes into the mind of the man who gazes at this picture. I thought of all this by snatches probably between my attacks of delirium—for an hour and a half or so before Colia’s departure.

‘Can there be an appearance of that which has no form? And yet it seemed to me, at certain moments, that I beheld in some strange and impossible form, that dark, dumb, irresistibly powerful, eternal force.”

—Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans. Eva Martin.

“Holy Saturday. The drama of Holy Week dies down for a moment. However, our thoughts race ahead, because they are hesitant about stopping near scenes of mourning, at physically repelling pietas, or by the corpse of Christ that has turned blue (as Mantegna saw it during a moment of religious dread). It is difficult to stay with a dead God, if only because his very death negates the logic of all consolations—doubt strikes not only the object of hope, but also its very possibility. We run away. Even though the tortured body of Christ rests in its grave, we live in the inevitable arrival of Sunday. The encouraging signs: rolled away stone, empty grave, angels, glory! It’s as if the final battle with the gates of hell is already behind us. But why does God wait nonetheless? Why does he leave us at the grave? Why is the One who is capable of rebuilding the temple in three days incapable of rebuilding it immediately?

The temptation to run away from the silence of Holy Saturday is not new. These same waters—disgust with the foolishness of an actual incarnation and an actual sacrifice—water the Docetist heresy. In the apocryphal Gospel of Bartholomew (dated back to the third century) the harrowing of hell occurs already on Friday, even before the deposition from the cross. However this only makes Christ’s tomb into a mere theatrical decoration, and Saturday a problem of rhetoric not philosophy. I believe that Irenaeus of Lyons, who thought the Savior was in hell from his death until his resurrection, has the backing of some weighty theological reasons.”

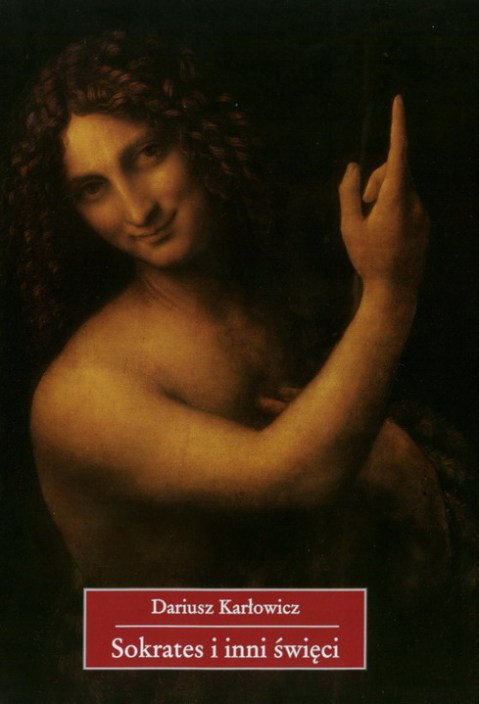

—Dariusz Karlowicz, Koniec snu Konstantyna [The End of Constantine’s Dream], my own translation.