Hell ain’t what it used to be! (Hans Memling, Last Judgment, stolen by pirates & bought by the city of Gdansk, Poland. YESSS.)

When was the last time any of you (who don’t attend fundamentalist churches) heard a good and theologically sound hellfire sermon? The last, no the only one, I’ve ever heard was in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Here it is in its glorious entirety if you need a memory refresher (BE AFRAID!):

Over the last two centuries Hell has been banished from the Catholic imagination more effectively than Adam and Eve from Eden. I suppose the last blows came sometime during the long 19th century dominated by Napoleon, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, and Feuerbach.

The infernal trenches of World War I gave hellfire a slight rebound. The whole messy experience cast hell from oblivion back into our world, but not the underworld. It became a truism to say that people not infrequently make hell on earth. The concentration camps and gulags of World War II firmly entrenched hell upon the face of the earth.

Now, to some extent, we also still half-heartedly believe that sin is its own punishment. But why can’t Hell be both the state after life and a state in this present life? I’m all for a Catholic both/and here.

Now, you might ask yourself, why is the author obsessing about hell? Reading the headlines has left me in a bit of a foul mood. Consider what the AP recently said about poverty in the United States:

“Four out of 5 U.S. adults struggle with joblessness, near-poverty or reliance on welfare for at least parts of their lives, a sign of deteriorating economic security and an elusive American dream.”

Four out of five is not a misprint as far as I know. It has unfortunately checked out on all the searches I’ve done so far. I’m still hoping it’s wrong, after all, this is supposed to be one of the richest countries in the world. Then again, our family of five has always been well below the poverty line, so it’s a little comforting to know we’re not alone.

Then this picture showed up on my social media radar as if to drive the point home:

“A true opium for the people is a belief in nothingness after death–the huge solace of thinking that for our betrayals, greed, cowardice, murders we are not going to be judged.” –Czeslaw Milosz

I also happened to be reading (because who doesn’t read five things at time?) the book-length dialogue between the then Cardinal Bergoglio and Abraham Skorka entitled On Heaven and Earth. There the future Pope Francis forcefully reminds us of the close tie between authentic religion and social justice:

“Hence the [classical] liberal conception of religion being allowed only in places of worship, and the elimination of religion outside of it, is not convincing. There are actions that are consistently done in places of worship, like the adoration, praise and worship of God. But there are others that are done outside, like the entire social dimension of religion. It starts in a community encounter with God, who is near and walks with His people, and is developed over the course of one’s life with ethical, religious, and fraternal guidelines, among others. There is something that regulates the conduct of others: justice. I believe that one who worships God has, through that experience, a mandate of justice toward his brothers.”

One should not forget that the mandate toward social justice is solely a Judeo-Christian invention. The pay raises of Caterpillar CEO Doug Oberhelman, coupled with the poverty awaiting most of us, signal a return to the much more cruel gods of Graeco-Roman religion. Whether we like it or not, we can look forward to a massive, but unintentional, experiment in comparative religion. It’s unavoidable, since I don’t foresee CEOs suddenly having epiphanies like this one:

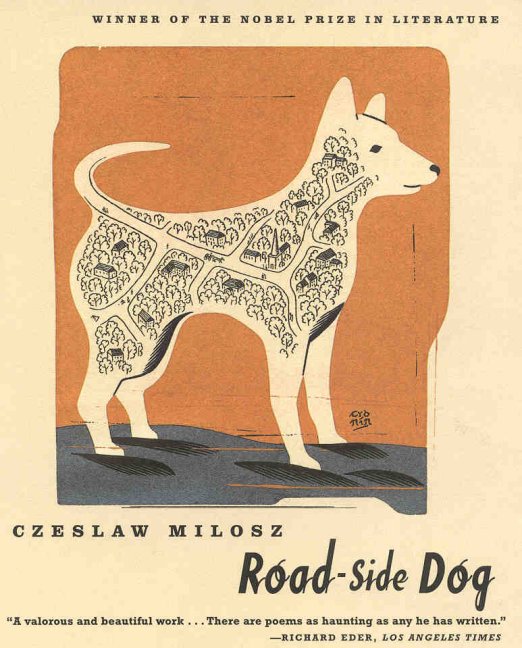

Finally, these perfidies of American betrayal and greed bring us to my dissertation topic (what else?), the poet Czeslaw Milosz. After you read a passage from one of his works below you will agree he also happened to have a finely-honed feel for theological reflection. The following reflection, which comes from the section “The Discreet Charm of Nihilism” (props to Bunuel) in the collection Road-Side Dog, turns Marx upside down, or at least shakes up a well-known phrase of his real good.

“Religion, opium for the people. To those suffering pain, humiliation, illness, and serfdom, it promised a reward in an afterlife. And now we are witnessing a transformation. A true opium for the people is a belief in nothingness after death–the huge solace of thinking that for our betrayals, greed, cowardice, murders we are not going to be judged.”

You might object by saying that you can be a nice lad or lass (even point out Sweden as a sociological example) without the afterlife and the threat of judgment hanging over your head. But Sweet Viking Jesus would tell you otherwise. Swedish ethics are influenced by revelation through and through, as is the rest of the West, and everyone influenced by globalism, meaning… pretty much everyone.

What’s more, those who aren’t believers (Swedes aren’t the only ones. Jag är ledsen!), but hang on to the Christian ethic of protecting the weak and the victims, are probably the worst fideists of all!

They are embedded in something they can’t justify, something whose origins they’ve willfully obscured, but deep down they know that empty phrases about Gilgamesh, Odin, or Kant won’t get them anywhere.

So, given where the world is heading, our eviscerated public square, and who is at the helm… how about we pray that there’s a Hell?

There is a caveat: nobody gets a free pass.

The musical coda is a song from Bill Mallonee that first got me thinking seriously about these issues way back when.