“The last few years, while writing my poetry, I’ve been concerned about not deviating from Catholic orthodoxy, although I’m not sure how it came out in the end,” says the author of The Land of Ulro in a letter to the pope (my own revised translation).

August 9th marked the deaths of both Maximilian Kolbe and Czeslaw Milosz. Cynthia Haven has written about how these two Poles have influenced the wider world in divergent ways that converge upon their Catholicism in the essay “The Doubter and the Saint.”

Granted, Milosz was much more of a believer than we tend to give him credit. There is even a fairly badly translated series of letters exchanged between Milosz and JP2 available online here.

One Goodreads commenter said The Stained Glass Elegies are “sad stuff” and added a frowning smiley. But so is much of history and, not infrequently, so is daily life. But what does God have to do with that?

August 9th was also the 68th anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing. All of these convergences somehow reminded me of two short stories penned by the postwar Japanese-Catholic writer Shusaku Endo in the collection Stained Glass Elegies.

The first one features the strange encounter between a child and Kolbe during his mission to Japan. Later on, as an adult, the person shocked at the news of that someone so cowardly looking (like a mouse) found the courage to give up his life for another.

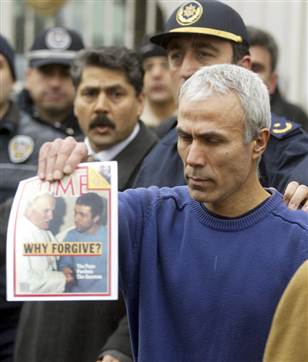

The other story involves a rich Japanese tourist visiting a Polish prostitute a severely economically depressed period in Poland and having an epiphany upon seeing a picture of Kolbe hanging on the wall (if I’m not mistaken) while waiting for her to undress.

All of this, in a roundabout way, brings me to a moving meditation on the blog City and the World about Nagasaki and Kolbe that I’d like to excerpt for you:

“…As I study the [picture of the relic, see below], I wonder what the appearance of this relic might have meant in an immediate postwar context. In 1949, the atom bomb’s effects on Nagasaki were still very visible: another of Mydans’ photos reminds us that the Pontifical Mass celebrated to mark four centuries of Christian faith in Japan took place within the ruins of a destroyed Catholic cathedral. Considering the relic itself, it strikes me that it is difficult to look at the shriveled fingers of the saint’s hand and the exposed bones of his forearm without thinking of the disfigured flesh of the atom bomb’s victims. Would the Catholics of Nagasaki have seen a link between Xavier’s body and the bodies of their kin? I can’t know for sure, but I also can’t help but wonder whether they might have done so.

“Considering the relic itself, it strikes me that it is difficult to look at the shriveled fingers of the saint’s hand and the exposed bones of his forearm without thinking of the disfigured flesh of the atom bomb’s victims. Would the Catholics of Nagasaki have seen a link between Xavier’s body and the bodies of their kin?”

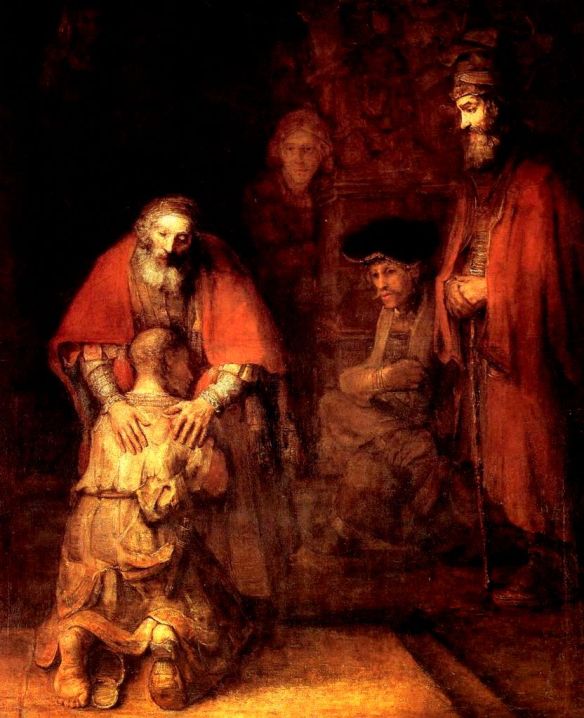

What are we to make of all of this theologically? Looking at the image of the Xavier relic in Nagasaki, I find myself thinking of the words of St. Maximilian Kolbe, who served as a missionary in Nagasaki in the 1930s and later lost his life at Auschwitz, having volunteered to take the place of another prisoner who had been chosen for execution. As Kolbe once wrote, ‘Hatred is not a creative force. Love alone creates.’ For Maximilian Kolbe, self-sacrificing love represented the only effective response to the horrors of which humankind is capable. This kind of love led Kolbe to give his life for another; the same love led Francis Xavier to leave his home and everything that was familiar to him to preach the Gospel in faraway lands. Underlying these and all other examples of self-sacrificing love is the more fundamental action of divine love, the love that led the Second Person of the Trinity to embrace our humanity and to accept death on the Cross for the sake of our redemption…”

You can read the rest here.

I’m still not quite sure what to make of all these connections, but I’ll add another one: Despite the Youtube description, below you will find an excerpt from the excellent Krzysztof Zanussi film about Kolbe, “Life for a Life.” You can find copies of this film scattered throughout the States. Unfortunately, only a few of Zanussi’s films are available in the States. I’d recommend “A Year of the Quiet Sun,” which features stunning (nearly silent) performances by Scott Wilson and Maja Komorowska. It is set in the devastation of postwar Poland.

===========

UPDATE: The whole film is available in Polish (with much German) on YouTube. The acting is good enough that you could watch it without knowing either one of those languages.