Beauty Will Save the World needs a new title to reflect the contribution it makes avant la lettre to recent debates. I suggest Beauty is Saving the World!

Paul Elie says all the great novelists are dead. But he’s dead wrong!

I’ve recently discovered that Randy Boyagoda resurrected Elie’s argument in the latest issue of First Things here. He starts out by venting:

“I’m sick of Flannery O’Connor. I’m also sick of Walker Percy, G. K. Chesterton, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Dostoevsky. Actually, I’m sick of hearing about them from religiously minded readers. These tend to be the only authors that come up when I ask them what they read for literature.”

[Below: Noah Baumbach tackles nostalgia overload.]

Even though Boyagoda is tired of those consumed with nostalgia for a literary Golden age he ends up conceding their point by agreeing with Elie. He even takes Elie one step further by going into a quasi-sociological analysis that culminates with David Shields as the master-theorist of decline. In a nutshell, Boyagoda’s argument is built around these assumptions:

“As welcome as Elie’s effort was as a conversation starter, he failed to answer some important questions, even while he candidly admits to be wrestling with them as he works on a novel of his own: Primarily, what constitutes ‘belief’ or ‘faith’ in literary terms, and how are we to evaluate the representation aesthetically, morally,theologically? [Interestingly enough Boyagoda does not answer this question!]… Nevertheless, Elie’s main point holds. Despite various idiosyncratic and veiled representations of religious experience in recent American fiction—in the works of Robinson, and also, with more qualifications, in the works of Toni Morrison [I object, see below], Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, David Foster Wallace, and others—most great contemporary writers don’t bother to engage the wholeness of experience for the great majority of readers.”

I’ll spare you a summary of the Shields part of the argument, but you can explore it in the link to Boyagoda’s essay above, or you can take a look at what Shields has to say in Reality Hunger.

Why a Richard John Neuhaus scholar would take the part of Shields over George Steiner is beyond me. Neuhaus never grew tired of singing the praises of Steiner. The great literary critic decisively argued that not only literature, but all of human reality, is dependent upon a Christian sacramental imagination. Let’s hope Boyagoda will not forget passages such as this one from Neuhaus while completing his RJN biography:

“In Grammars of Creation, more than in his 1989 book Real Presences, Steiner acknowledges that his argument rests on inescapably Christian foundations. In fact, he has in the past sometimes written in a strongly anti-Christian vein, while the present book reflects the influence of, among others, Miri Rubin, whose Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture is credited in a footnote. Steiner asserts that, after the Platonisms and Gnosticisms of late antiquity, it is the doctrines of incarnation and transubstantiation that mark ‘the disciplining of Western syntax and conceptualization’ in philosophy and art. ‘Every heading met with in a study of ‘creation,’ every nuance of analytic and figural discourse,’ he says, derives from incarnation and transubstantiation, ‘concepts utterly alien to either Judaic or Hellenic perspectives—though they did, in a sense, arise from the collisions and commerce between both.'”

“Any coherent understanding of what language is and how language performs, that any coherent account of the capacity of human speech to communicate meaning and feeling is, in the final analysis, underwritten by the assumption of God’s presence,” says Steiner in Real Presences.

Yesterday we explored why Elie strategically exempted poetry from his argument here. The poets listed in that post are some of our most gifted writers. The novelists you’ll find below are of the same caliber. These writers have won countless awards writing fiction that will last long enough for later generations to envy our Golden Age of religious fiction.

I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to say that our generation of writers exceeds the Eliot-Auden and Percy-O’Connor generations. Novels are notoriously difficult to excerpt, so I’ll stick mostly publisher blurbs and a few sidebars to justify some of the choices that might strike you as unusual. At the bottom of this post there’s also a list of very honorable mentions.

As usual, do follow the unique links provided below if you’d like to help me put some diapers on little Rosman butts. Please also consider donating directly through the link in the upper right hand corner of the homepage.

Twenty-four years after her first novel, Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson returns with Gilead, an intimate tale of three generations from the Civil War to the twentieth century: a story about fathers and sons and the spiritual battles that still rage at America’s heart. Writing in the tradition of Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, Marilynne Robinson’s beautiful, spare, and spiritual prose allows “even the faithless reader to feel the possibility of transcendent order” (Slate). In the luminous and unforgettable voice of Congregationalist minister John Ames, Gilead reveals the human condition and the often unbearable beauty of an ordinary life.

A novel about convent life at the turn of the century? Hardly the makings of a page-turner, yet Ron Hansen’s Mariette in Ecstasy is a gripping, even life-changing book. For the Sisters of the Crucifixion, each day is a ceaseless round of work, study, and prayer–one hardly separate from the other. Their daily life is itself an act of devotion, caught by Hansen in a series of illuminated tableaux… Into this idyll comes Mariette–young, pretty, devout, but, as her father says, perhaps “too high-strung” for the convent. Prone to “trances, hallucinations, unnatural piety, great extremes of temperament, and, as he put it, ‘inner wrenchings,'” Mariette scalds her hands with hot water as penance, threads barbed wire underneath her breasts while she sleeps, and is convinced Jesus speaks to her. Her very glamour disturbs the gentle rhythm of the nuns’ lives. But when she begins bleeding from unexplained wounds in her hands, feet, and sides, the convent is thrown into an uproar. Is Mariette a saint? Or just a lying, hysterical girl? Where do we draw the line between madness and faith, mysticism and eroticism, the life of the spirit and that of the world?

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is the story of a dramatic year in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley. Annie Dillard sets out to see what she can see. What she sees are astonishing incidents of “beauty tangled in a rapture with violence.”

Her personal narrative highlights one year’s exploration on foot in the Virginia region through which Tinker Creek runs. In the summer, Dillard stalks muskrats in the creek and contemplates wave mechanics; in the fall, she watches a monarch butterfly migration and dreams of Arctic caribou. She tries to con a coot; she collects pond water and examines it under a microscope. She unties a snake skin, witnesses a flood, and plays King of the Meadow with a field of grasshoppers. The result is an exhilarating tale of nature and its seasons.

[This book is a hybrid: autobiography, fiction, theology, and biology. But if you’re so inclined there are other Dillard novels to choose from.]

Among the characters you’ll find in this collection of twelve stories by Tobias Wolff are a teenage boy who tells morbid lies about his home life, a timid professor who, in the first genuine outburst of her life, pours out her opinions in spite of a protesting audience, a prudish loner who gives an obnoxious hitchhiker a ride, and an elderly couple on a golden anniversary cruise who endure the offensive conviviality of the ship’s social director.

Fondly yet sharply drawn, Wolff’s characters in The Garden of the North American Martyrs stumble over each other in their baffled yet resolute search for the “right path.”

[Short stories are fiction, right?]

Jayber Crow, born in Goforth, Kentucky, orphaned at age ten, began his search as a “pre-ministerial student” at Pigeonville College. There, freedom met with new burdens and a young man needed more than a mirror to find himself. But the beginning of that finding was a short conversation with “Old Grit,” his profound professor of New Testament Greek. “You have been given questions to which you cannot be given answers. You will have to live them out—perhaps a little at a time.”

“And how long is that going to take?”

“I don’t know. As long as you live, perhaps.”

“That could be a long time.”

“I will tell you a further mystery,” he said. “It may take longer.

In the backwoods of Mississippi, a land of honeysuckle and grapevine, Jewel and her husband, Leston, are truly blessed; they have five fine children. When Brenda Kay is born in 1943, Jewel gives thanks for a healthy baby, last-born and most welcome. Jewel is the story of how quickly a life can change; how, like lightning, an unforeseen event can set us on a course without reason or compass. In this story of a woman’s devotion to the child who is both her burden and God’s singular way of smiling on her, Bret Lott has created a mother-daughter relationship of matchless intensity and beauty, and one of the finest, most indomitable heroines in contemporary American fiction.

By opening with a long epigraph from St. Augustine’s Confessions (in the original Latin, no less), Clark’s ambitious, atmospheric rumination on good, evil and the gray area in between announces intentions far loftier than those of the standard dime-store detective novels to which the book bears an intentional but superficial resemblance. Set in St. Paul, Minn., in the bleak winter of 1939, this high-brow thriller retains enough lowdown grit and grime to qualify as both a suspenseful read and a surprisingly touching character study. When two young “dime-a-dance” girls are murdered, tough-as-nails homicide cop Lieutenant Wesley Horner hones in on eccentric recluse and amateur photographer Herbert White as the prime suspect. Looking like a cross between Humpty Dumpty and Paul Bunyan, and equally obsessed with Hollywood starlet Veronica Galvin and the voluminous scrapbooks and journals he keeps in order to compensate for his (narratively convenient) memory loss, White takes the fall with sympathetic dignity: astute readers will have fingered the real culprit many pages earlier. The true mysteries in Mr. White’s Confession are psychological: Horner’s morally suspect relationship with teenage drifter Maggie is particularly fascinating. Having previously written a biography of James Beard (The Solace of Food), a cultural history of the Columbia River (River of the West) and a critically lauded first novel (In the Deep Midwinter), Clark here seesaws, most often successfully, between hard-boiled cliches and an earnest, self-conscious concern with the natures of memory and love.

A.G. Harmon’s A House All Stilled, won the Peter Taylor prize for fiction. Like the great Peter Taylor, Harmon is a Southern novelist whose prose is both precise and evocative, reflecting a deep relationship to the land and the mystery of familial relationships over several generations. But Harmon’s novel also has religious and symbolic resonances that Flannery O’Connor would recognize and salute. The novelist Doris Betts, who selected this novel for the Taylor Prize, adds yet another literary comparison: “Harmon’s style,” she writes, “has deft flicks of description and insight, similar to the way Graham Greene might toss out a selected metaphor then move on.” A House All Stilled is an auspicious debut for a major new talent in literary fiction.

[The greatest living writer you’ve never heard of. One of you should start a Kickstarter campaign to raise money for his second novel.]

Morrison, in her sixth novel Jazz, enters 1926 Harlem, a new black world then (“safe from fays [whites] and the things they think up”), and moves into a love story–with a love that could clear a space from the past, give a life or take one. At 50, Joe Trace–good-looking, faithful to wife Violet, also from Virginia poor-times–suddenly tripped into a passionate affair with Dorcas, 18: “one of those deep-down spooky loves that made him so sad and happy he shot her just to keep the feeling going.” Then Violet went to Dorcas’s funeral and cut her dead face. But before Joe met Dorcas, and before her death and before Violet, in her torn coat, scoured the neighborhood looking for reasons, looking for her own truer identity, images of the past burned within all three: Violet’s mother, tipped out of her chair by the men who took everything away, and her death in a well; for Joe, the hand of the “wild” woman, his mother, that never really found his. And all of the child Dorcas’s dolls burned up with her mother and her childhood. Truly, the new music of Harlem–from clicks and taps of pleasure to the thud of betrayed marching black veterans with their frozen faces–“had a complicated anger in it.” Were Joe and Violet substitutes for each other, for a need known and unmet? At the close, a new link is forged between them with another Dorcas. One of Morrison’s richest novels yet.

[What other Catholic novelists do you know that use purgatory as a leitmotif?]

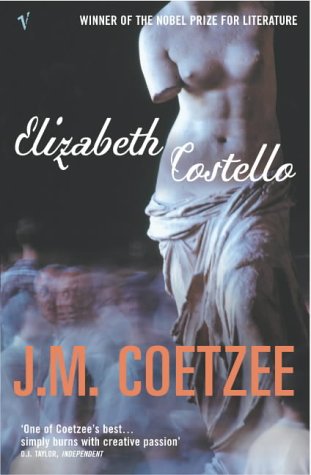

I‘m going to be a little coy and recommend you read my post here where I argue Coetzee is possibly our greatest Christian novelist. Elizabeth Costello is probably his best novel, although I still haven’t read the UK edition of The Childhood of Jesus. It comes out this September in the US.

===============

The first installments in this series are “A Fish Rots from the Head Down” and “Fresh Caught Fish: Top 10 Living Religious Poets.”

Just in case you think any (or all) of the above choices don’t qualify, here are twelve literary apostles I left off this list due to time constraints: David James Duncan, PIckney Benedict, Suzanne Wolfe, John L’Heureux, Mary Doria Russell, Hwee Hwee Tan, Larry Woiwode, Dan Wakefield, David Lodge, Andre Dubus III, Elie Wiesel, and Gene Wolfe. In other words, (actually, in the words of Randy Boyagoda), “We are not, in the end, alone.”

In fact, there are so many companions for the road already that I wonder whether I’ll have enough time to read Elie’s novel when it comes out. My present list just keeps expanding and expanding so much that I’m tempted to give up: